| Statues – what’s the point? | ||||||

| William Morris, born in 1834, was a British textile designer, poet, novelist, translator and socialist activist. He was a key person in the British Arts and Crafts Movement. His legacy can be seen in various National Trust homes. He is also remembered for his 1880 maxim: “Have nothing in your house which you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful”. So then, in my house, I have to try to be useful. As for the contents of the house, I regret to say that they are far from uniformly useful, and few of the things which are not useful manage to be beautiful. Even during this period of enforced idleness, we have not succeeded in making more than a token effort to rid ourselves of the things which occupy space, but do nothing to earn their keep. We excuse ourselves by saying that we would need to make an appointment at the tip and, even then, would only be permitted to go to dispose of things if it was an essential journey. Having had many of these redundant objects for very many years, it’s difficult to argue that they’ve now suddenly become a matter of life or death. After this is over, though, I think that we shall need to hire a professional declutterer to carry out regular raids on our junk. But it is not only in our private space that we need to heed William Morris’s maxim. It is also in the public space. It is now proposed that we should make space for one more statue, this time of Captain Tom with his walking frame. So then a little different to the ones of generals on horses. Rather than being a symbol of war or our imperial past, he captured our support with his optimism and modesty during our long Covid imprisonment. The statue was made a while ago by a Derbyshire firm, obviously anticipating his demise and no doubt wishing to be first in the statuary market. I have some sympathy with the proposal, but I’m not entirely sure that the statue will really improve our remembrance of his contribution to our lives. Most of us will not actually go to see it and, wherever it’s put, it will eventually cease to be seen, just like the statues of past governors of our empire. Succeeding generations will have no idea who he is or why he is celebrated. Statues of people notable in one generation inevitably fade into the background, become invisible, for those without the living memory of what made them famous – and this despite any words engraved on the plaque. But of course statues are, at the moment, a hot topic. Many people want to tear them down. Those who did actually tear down the statue of Edward Colston, the man who mixed slave-trading with great philanthropy towards the people of Bristol, have been prosecuted for criminal damage. They are due to appear before the Crown Court later this year. They could have elected to be dealt with in the magistrates court. Obviously though they hope that, although what they did was clearly an offence, they will be acquitted by a sympathetic jury. But in the meantime, the pressure for decolonising our public statuary continues. Exeter city council has lead the way with its initial decision to try to move the statue of General Sir Redvers Buller. An ‘equality impact assessment’ from the Exeter Council task force appointed to look into the question read: “The General Buller statue represents the patriarchal structures of empire and colonialism which impact negatively on women and anyone who does not define themselves in binary gender terms. The consultation will need to ensure that the views of women, transgender and non-binary people are captured and given due weight.” What?! Buller was head of British forces during the Second Boer War and was in overall charge when a battle took place in which 3,000 of his men were wounded, captured or killed when fighting the Boers, something for which he was much criticised. Nonetheless, Buller, as someone born in Devon, was awarded the freedom of Exeter and commemorated with the statue. Of course, fighting the Boers meant that he was fighting against the white regime in South Africa – although probably not out of concern for the repression of the black population by the Boers. But it does rather illustrate the difficulty of judging people from a previous age by our standards. There was undoubtedly a reason why he should not have been rewarded with a statue in the first place – he was a bad general - but does that mean that he should be removed now simply because he undoubtedly represented and conformed to the thinking of his time? Yet while the far left exaggerates the impact of statues for its own ends, so too does the right. The housing minister, Robert Jenrick, wrote an article declaring that he would not allow the “baying mob” to “censor” or “erase” our past: “I will not hesitate to use my powers as secretary of state in relation to applications and appeals involving historic monuments”. The government’s official view is that “such monuments are almost always best explained and contextualised, not taken and hidden away”. Such rhetoric plays to the right wing part of the gallery but it overplays the importance of statues to our national identity. It suggests that these objects recount our history and are meaningful to most of us. But most of them don’t and aren’t. Of course the Romans were apparently much inspired by their statues, bathing them and laying flowers around their pedestals. I haven’t seen similar emotions being engaged in Britain recently. Why, then, should we erect more statues that don’t really enhance our public spaces and that inspire neither awe nor adulation? This goes for statues of which both the right and left would approve. Sadiq Khan’s pompously named ‘Commission for Diversity in the Public Realm’ is currently scrutinising London’s statuary to see which white, male, colonial heads can roll. It will undoubtedly suggest instead a group of transgendered, non-white, female and gay figures to be reproduced in bronze or granite. But surely these too will become part of the furniture, and this will happen even more quickly than normal if, as is very likely, they are people whom we haven’t heard about before and so have not entered the public memory. So then, why bother? Around the world there are many statues that actually fit in with William Morris’s wish that works of art should speak to us and enhance our lives. There are many beautiful works in museums which could be copied and put on display, perhaps on rotation. But there are even now statues on the streets which make us pause and think. There is the Swedish statue “The Woman with the Handbag”, which pays tribute to the woman who handbagged a neo-Nazi protester.

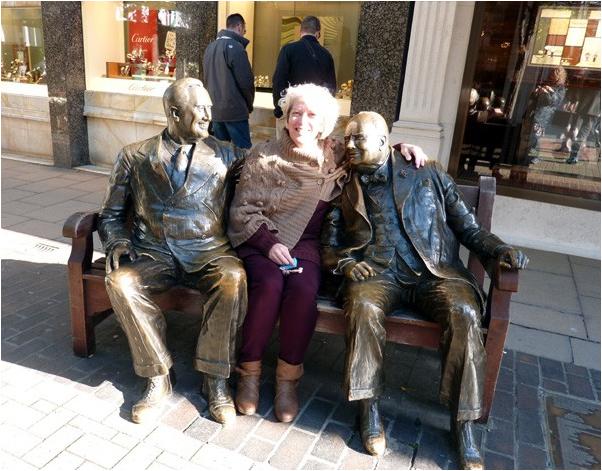

In Bond Street in London there is a statue called Allies, showing Churchill and Roosevelt in conversation on a bench, which avoids the formal style normally used for the depiction of great men - and even allows audience participation.

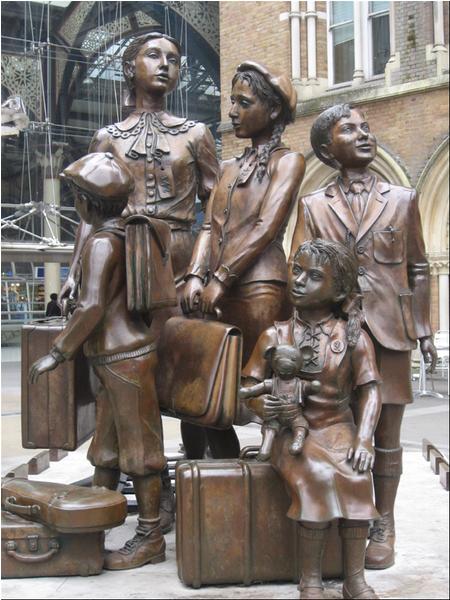

Then there is the statue at Liverpool Street Station commemorating the Kindertransport. This was the time In 1938 and 1939 when ten thousand  unaccompanied Jewish

children were transported to Britain from

Germany and Austria to escape persecution.

Those children arrived at Liverpool Street

station to be taken in by British families and

foster homes. Mostly they never saw their

parents again. unaccompanied Jewish

children were transported to Britain from

Germany and Austria to escape persecution.

Those children arrived at Liverpool Street

station to be taken in by British families and

foster homes. Mostly they never saw their

parents again.We have more than enough bronze figures in our streets which none of us know anything about. If we have some genuinely new heroes, then I might make an exception, but I think there’s a good argument against any more statues commemorating particular individuals, or at least keeping them in place for any lengthy period. After say 20 years, maybe they could go off to a national memorial park and information centre somewhere. This would allow those interested to see them and learn about who they were in some depth. Let us instead confine new works on our streets to things of beauty or statuary which makes us think. Paul Buckingham 10 February 2021 |

||||||

|

|