As Juliet asked, "What's

in a name?" Well, actually quite a lot.

- A number of years ago,

I went to a conference dealing with the law relating to the protection

of intellectual property rights and brands in particular. Being

young and naive, I was astonished at how seriously the speakers

took the need to protect their clients' brands. Now protection

comes in a number of different

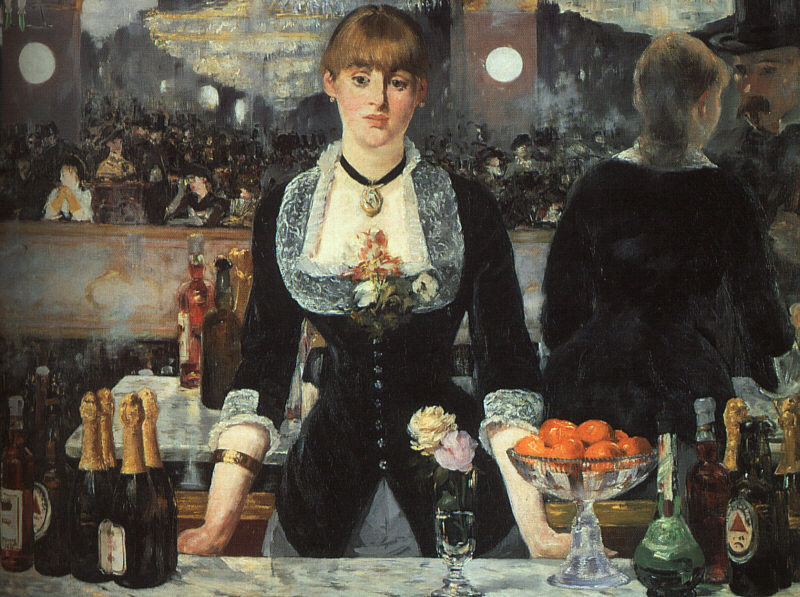

forms, including patents, copyrights and trademarks. Patents confer a monopoly, to encourage inventiveness, and are limited (with minor exceptions) to a life span of only 20 years and copyright exists for the life of the creator of the work plus 70 years to give value to something which can often be copied for almost nothing. A trade mark, though, is for ever. The bottles of Bass Pale Ale shown on the bar in the Manet 1882 painting ‘Bar aux Folies-Bergère' have on them the first ever registered trade mark. It was registered in 1876. And it is still being used today.

Of course, the point of all this protection is supposedly to stop people passing off their products as yours, so cashing in on your reputation or taking advantage of your inventiveness or creativity. But brand management is now a very big industry. Large companies such as Nike are valued in terms of the underlying value of their brands. If though a brand gets into trouble, as Ratners did many years ago or as Cadbury's with their recent Salmonella problems, and now as Matel / Fisher Price have done with the recall of 7 million defective toys, then the value of the shares in the company can be hit badly. Brand value is based on consumer trust, a fragile thing.

But brands are used to inflate enormously the price of what is sold. The other day I heard an interview on the radio with the MD of a company which makes expensive upmarket prams, formerly used by royalty and now used by the new royalty - the film stars in Hollywood. They are in fact all made cheaply in China, but it was claimed that the ‘added value' produced by the design and marketing, justified that high price. There is a large market in the Czech Republic where they sell faked goods in vast quantities. It is just a few hundred metres over the border from Germany. Reasonable quality ‘Lacoste' shirts are sold for 10 euros - less than the price you would pay for an ordinary shirt, which means that they must cost far less than this to manufacture. And this is common to most of the clothes, bags and other fashion items which are sold there. The real thing often costs relatively little to manufacture, but the name associated with it enables the customer to be charged a very high price, even if the quality is no better than the non trade-marked product and, as we have seen, can be very poor indeed.

So why do we buy into brands? Well, I suppose firstly it is because it is a relatively efficient way of living your life. When we have to buy something of which we have no recent experience, we spend a lot of time looking at what is available and at specialist reports. Think of the immense waste of time if we had to do that every time we bought a new packet of tea. Why spend time trying all the cheaper own-brand breakfast cereals when you already like the one you normally buy? If you like Channel No. 5, why risk a substantial sum of money on buying something which you may not like as much? And which husband would dare to buy Tesco No 5 for his wife anyway? - which brings us to the second reason - vanity. We like to be seen to have bought something which is fashionable, approved of by others. And once we have a certain amount of money, we don't want to be seen as penny-pinching either.

The trouble with the whole brand industry, however, is that it all looks rather anti-competitive. Much legislation is directed at preventing money from being extracted from consumers by unfair practices. The whole brand industry, however, supported by a raft of civil and criminal laws to uphold it and the assistance of the police and customs, is directed at precisely the opposite - extracting money from customers in exchange for an illusion - the illusion that goes with having bought into a brand. And which is really the greater rip-off - to be sold something for £10 which may not work or last or to be sold apparently the same thing for £100, which is perhaps more likely to work or last, but which still only cost £5 to produce? So, I'm with Juliet - what's in a name?