| Democracy today | ||

| |

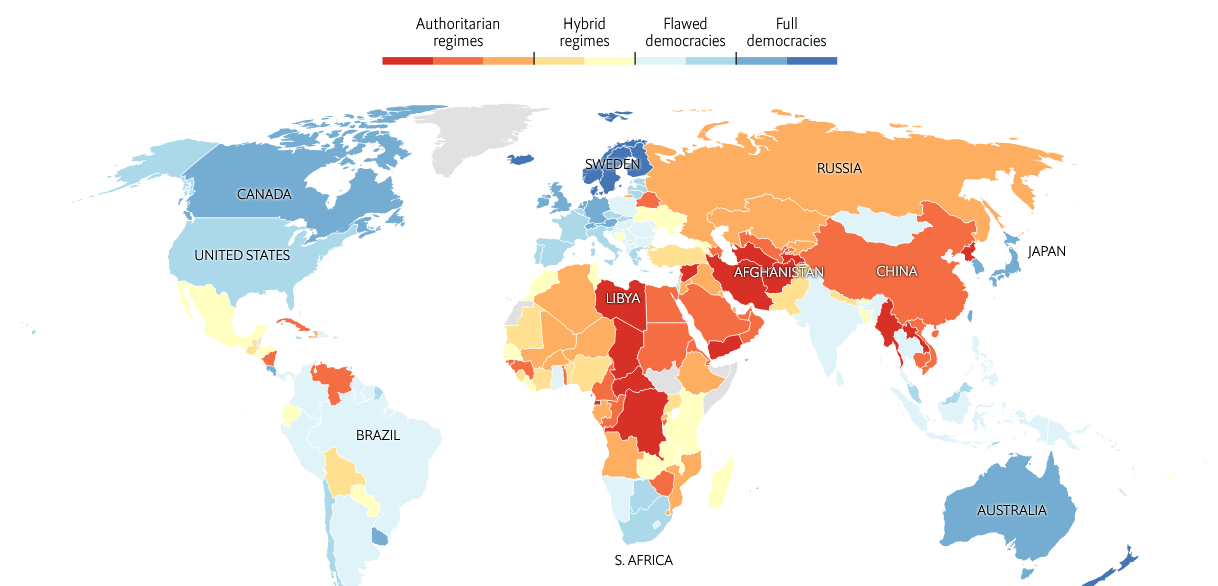

It’s depressing that, as we are trying to find ways to shore up the democratic government in Ukraine, the latest Democracy Index, published on 10 February by the Economist Intelligence Unit, continues to show a gradual decrease in the extent of democracy in the world. At 5.28 for 2021 (5.37 in 2020) it is the lowest since the index was first produced in 2006. The index is based on 60 indicators in 5 categories with a possible score in each of 0 to 10. The five categories are:

The average of all of these indicators becomes a country’s score. The countries are then divided into: 1. Full Democracies with an overall score greater than 8; 2. Flawed Democracies with a score between 6 and 8; 3. Hybrid, 4 to 6; and 4. Authoritarian with less than 4. The annual survey finds that more than a third of the world’s population live under authoritarian rule, while only 6.4% enjoy a full democracy.  It turns out that the UK has a score of 8.2, so a full democracy, although not quite as full as Norway (9.75), Ireland (9) or Germany (8.67). It seems that most of the other countries in Europe are ‘flawed democracies’, as is the United States (7.85), courtesy of Trump. At the other end of the range we find places such as North Korea and Myanmar, which barely register, then very slightly more democratic countries like Syria and Saudi Arabia and, a little higher up on the list (would you believe), China, Belarus, and then Russia with a score of 3.24. I suspect that Russia won’t be quite as high on the list in the next index. Democracy is in fact a difficult thing to define. We talk of the will of the people, but this is an over-simplification. The phrase tells us what our aim is, but not how we get there. Although broken down further into numerous sub-categories, the main five measures now used by the EIU indicate the degree of complexity which can be involved in defining democracy in modern societies and how the expression of the will of the people can be encouraged or discouraged. Of course if we look back into the history of democracy here in the UK, we can see that it has evolved. In 1774, the parliamentarian Edmund Burke said: “Your representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays instead of serving you if he sacrifices it to your opinion.” So then, not exactly the will of the people, but the combined will of the MPs elected to Parliament and assumed to represent the will of the people. Wanting a greater say in the governance of this country, some 60 years later, in 1838, ‘The People’s Charter’ was published by the Chartists, a movement for political and social reform in the United Kingdom. Amongst other things, it demanded: voting by secret ballot to elect members of parliament, an end to the need to own land in order to be an MP, pay for Members of Parliament and an annual election to Parliament. At first glance, there appears to be no conflict between the statement made by Burke and the demands of the Chartists. But the combined effect of the requirement that MP’s be paid a salary (so that non-toffs could stand for election) and having an annual election to Parliament. would have made Burke’s conception of democracy very difficult to achieve in practice. They would actually combine to make the MP a proxy for his constituents rather than being a representative able to vote in accordance with his ‘judgement’. Why? Because he would risk being unceremoniously kicked out at the next yearly election and lose his salary at the same time. We have instead provided pay for MPs, but given them 5 years between elections, time perhaps for votes on particular policies to be forgotten in favour of a broader assessment of their contribution to their constituents. But the election cycle is still critical to MPs. The effect of controversial decisions in the year leading up to an election can be crucial, simply because there isn’t time for the mists of time to do their work. Which is why governments try to adapt their policies to the election cycle. The fact that people are now career politicians, relying on their salaries (other than Rees-Mogg), makes them beholden to their parties and so makes their role as independent thinkers much more fragile. This is underlined by looking at the large number of commentators, like Madeleine Albright, who are telling us about what they have always perceived to be the real character and motivation of Putin. In the light of this, why is that we’re in this mess? Why did we allow ourselves to get into bed with his oligarchs; rely on Putin for our oil and gas? Obviously we can say ‘follow the money’, and that would be right, but in my view it speaks to rather more than that. We have a pact with our politicians. We know that asking electors to make detailed decisions about the future direction of the country cannot work, and so we pay our MPs to be our representatives, to get to analyse the details and make those decisions accordingly. Impliedly, we are asking them to decide things based, not on what they perceive to be the political exigencies of a short-term election cycle, but for the long-term good of the country. How deluded are we! The only people seemingly working on long term plans are Putin and Xi Jinping. Is that what it takes to engage in long term strategy? It seems so. So how are our democratically elected ‘representatives’ coping in our attempt to defend another democratic country - Ukraine (Democracy index score 5.7)? I saw quite a lot of the debate in Parliament on the day of the invasion of Ukraine by Putin. Despite having a liar and a fool as Prime Minister, with the loss of credibility that produces in the outside world, the debate showed most of our parliamentarians in what I thought was generally a good light. They were actually doing their job as our representatives, asking sensible questions and making sensible comments. They accepted that in making life hard for Putin, we would be making life difficult for ourselves. How easily they’ll be able to sell that to the people they represent remains to be seen. A notable addition to the armoury we can employ against aggressors, however, is international law, with internationally agreed definitions of the sorts of egregious crimes we see accompany acts of aggression, together with the infrastructure required for prosecutions and so extended prison time for offenders. I was therefore delighted to hear a number of MPs invoking international criminal law. They were urging, quite rightly, that we should engage in a major information campaign. We should explain in clear terms to Russian politicians and the people in charge of the Russian armed forces that they are laying themselves open to prosecution at the ICC, with the probability of lengthy prison sentences. For many years, we have had prosecutions for genocide and war crimes – a failure to observe the normal rules of war, for instance by indiscriminate bombing causing civilian casualties. A number of pathological former dictators have been tried at the Hague. Some are now in prison or have died during their trials. These are often some years after the offence has taken place, when they have ceased to be able to wield the power needed to protect themselves. We have to make it clear to all involved on the Russian side, whether the top brass or politicians that any visit into the rest of the world at any time in the rest of their lives could result in their arrest. Perhaps we ought not to point out that their nemesis would come even more quickly if they lose the protection of their great leader. We wouldn't want them forming a protective circle. 26 February 2022 Paul Buckingham |

|

|

|